Making better places: The Challenge of Social Cohesion | JOHN TIBBITT from Policies for Places

In the face of increasing social inequality, migration, social exclusion and declining social mobility the concept of social cohesion now features prominently in discourse about communities both in academic literature and in social policy debates, yet despite its widespread use by academics, policy-makers and public officials, it is a concept whose succinct definition remains elusive.

What is social cohesion?

The notion of social cohesion revolves around ideas of strong social bonds, a sense of identity and of trust. It is about how connected we feel to others, the extent we feel solidarity and empathy with others and about how much we trust each other.

International organizations have provided more formal definitions which incorporate these ideas. The Council of Europe for example, defines social cohesion as ‘the capacity of a society to ensure the wellbeing of all its members, minimizing disparities and avoiding marginalization to manage differences and divisions and ensure the means of achieving welfare for all members’. The OECD sees social cohesion as a concept that rests on three independent ‘pillars’: social inclusion, social capital and social mobility. For the OECD a cohesive society is one that ‘works towards the well-being of all its members, fights exclusion and marginalization, creates a sense of belonging, promotes trust, and offers its members the opportunity of upward mobility’.

There are many researchers and organizations which give emphasis to particular aspects of the concept and the lack of an agreed definition can be problematic when it comes understanding the factors driving cohesion, the interactions between them, and the measurement of levels of cohesion in societies or communities. This complexity does not help either in operationalizing the concept at local level as a basis for determining policy interventions to promote cohesion or the benefits which flow from them.

Policy options

The definitions of social cohesion provided by International organizations like OECD and the Council of Europe alert policy-makers and political leaders to the importance of finding policies which encourage and support sustainable social relationships in communities, and which promote collective and individual well-being. Cohesion is a property of place: cohesive communities promote well-being and the quality of life. Organizations such as OECD have provided long lists of indicators relating to the range of dimensions relevant to the promotion of cohesion, and It is immediately obvious that addressing social cohesion requires action in a wide range of policy areas. These will include:

- Education to promote inclusive learning, equality of opportunity and civic values and skills;

- Economic policies to promote decent jobs and adequate resources for public spending to sustain community services;

- Social policies aimed at reducing poverty and providing income support for vulnerable people;

- Governance arrangements which promote civic participation and active citizenship;

- Community engagement policies to develop and support community initiatives and strengthen social networks;

- Equalities policies which respect the rights of all people irrespective of race, gender, religion or sexual orientation.

Actions in all of these areas can promote social cohesion, the most effective package depending on the specific circumstances of particular communities. Some relevant actions are predominantly central government functions, but local government and third sector organizations have scope to intervene with local measures in all these policy areas too.

Causes or consequences

It would seem that almost any area of social policy can have some impact on social cohesion. However, to identify an appropriate package of policy initiatives there is a need to disentangle the range of variables associated with the concept. and to be clear about causality.

A recent review identifies several strands of analysis which demonstrate factors which are causally related to social cohesion. One such is wealth and in particular wealth inequality which brings about negative effects on social cohesion. Another strand relates to the demographic composition of a community, especially to diversity and levels of migration, although the relationship with cohesion can be complicated. Some argue that diversity itself can lead to greater levels of perceived cohesion. On the other hand it seems that segregation as distinct from diversity leads to negative impacts. A further strand of analysis revolves around the role of education and lifelong learning. It is argued that education can have a major influence on social cohesion as it can promote economic opportunities and support common norms and values and encourage civic and community participation, all aspects which are seen as important for developing a cohesive communities.

But just as these factors can be drivers of social cohesion (positively or negatively) social cohesion itself drives other outcomes especially those relating to greater well-being, both individually and collectively and greater pro-social behaviour.

An aspiration, a process or an outcome?

These confusions and uncertainties around the definition of social cohesion, the causality of factors associated with the generation of cohesion, and their operationalisation in policy terms seem not to have undermined its popularity among politicians and policy-makers. For some, social cohesion can be a convenient ‘generic blob’ as Moustake puts it, where dimensions interact with each other equally and in unspecified ways. In the absence of any understanding of the interactions between factors policy making follows a more or less ‘grapeshot’ approach which suggest social cohesion is pursued more as an attractive aspiration than with any more specific outcomes in mind.

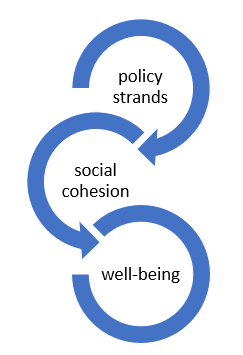

Alternatively, policies can be seen as the building blocks of cohesion in a process in which policy initiatives contribute to a broad objective of working towards stronger, thriving communities and improved well-being for people and places. In this sense social cohesion will always be a work in progress and a step towards other social policy objectives rather than an end in itself.

If social cohesion itself is to be an explicit policy outcome then its definition and measurement become crucial. There needs to be a way of identifying the efficiency and effectiveness of different actions in meeting the objective and we need some kind of criterion by which to establish whether or not a cohesive community is in place.

Social cohesion or well-being and happiness?

If, as the discussion on causality above suggests, social cohesion is a means to deliver well-being, and given the complex relationship between factors contributing to social cohesion, perhaps it is more helpful for policy-makers and politicians to focus directly on well-being rather than social cohesion as an intervening concept. There is significant research related to well-being. A recent report summarizes the most important factors that determine individual well-being. The single biggest predictor of adult well-being is emotional health at age 16. Strong communities and positive relationships are major drivers of individual and collective well-being (although studies also show that social capital is declining) and that 6 factors (trust, generosity, social support, freedom, income and health) explain 76% of the variation in well-being across countries. Other important influences relate to the quality of the physical environment, exposure to nature, job quality and unemployment.

The OECD has devised a comprehensive well-being framework and approach to its measurement. Ultimately however well-being rests on the lived experience of people in the place they inhabit. The challenge is to understand how lived experience and perceived well-being change in the light of policies aimed at building well-being.

There are suggestions too that happiness should be seen as a valid measure of social progress and a goal of social policies. Happiness and well-being should be explicit objectives in community development achieved through policies to build purpose and meaning into peoples’ lives. There are now a series of World Happiness reports. Based on data and analysis available in a series of regular World Happiness Reports, a cross-country comparative study of demonstrates how happiness can be enhanced in different ways. Despite different emphasis on such factors as lifelong learning, economic and environmental development or work-life balance, health and family, it is consistently clear that quality social relationships and trust are crucial to happiness and wellbeing.

Maybe it is time for policy-makers to be less concerned with the intricacies of social cohesion in favor of creating quality places which stimulate well-being and happiness.

Source: Susbtack

- PASCAL Activities:

- PASCAL Themes:

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version- Login to post comments